Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: An Old Story with New Ideas

Article information

Abstract

Years before insulin was discovered, anti-inflammatory sodium salicylate was used to treat diabetes in 1901. Intriguingly for many years that followed, diabetes was viewed as a disorder of glucose metabolism, and then it was described as a disease of dysregulated lipid metabolism. The diabetes research focused on the causal relationship between obesity and insulin resistance, a major characteristic of type 2 diabetes. It is only within the past 20 years when the notion of inflammation as a cause of insulin resistance began to surface. In obesity, inflammation develops when macrophages infiltrate adipose tissue and stimulate adipocyte secretion of inflammatory cytokines, that in turn affect energy balance, glucose and lipid metabolism, leading to insulin resistance. This report reviews recent discoveries of stress kinase signaling involving molecular scaffolds and endoplasmic reticulum chaperones that regulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. As we advance from a conceptual understanding to molecular discoveries, a century-old story of inflammation and insulin resistance is re-born with new ideas.

INTRODUCTION

Insulin resistance is a major characteristic of type 2 diabetes, which affects more than 250 million people worldwide [1]. Since insulin resistance is as an early and requisite event in the development of type 2 diabetes, understanding the cause of insulin resistance and identifying therapeutic intervention to treat insulin resistance have a global significance [2]. It is well established that obesity is a major cause of insulin resistance, and weight loss is known to improve insulin sensitivity in diabetic subjects [3]. However, the underlying mechanism by which obesity causes insulin resistance remains unclear. A number of interesting hypotheses and pathways have recently emerged that individually or collectively can explain the important link between obesity and insulin resistance [4,5].

One of the most exciting topics in recent diabetes research is the role of inflammation in type 2 diabetes. In 1993, Hotamisligil et al. [6] reported the role of adipose expression tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in obesity-linked insulin resistance. This was immediately followed by a landmark discovery of obese (ob) gene by Zhang et al. in 1994 that led to a frantic search and identification of a host of adipocyte-derived hormones, such as leptin and adiponectin, that potently regulate glucose homeostasis [7,8]. The birth of "adipocentric" view of diabetes has taken place. Despite the early discovery of TNF-α as a novel inflammatory cytokine to regulate glucose metabolism, the role of inflammation in diabetes was not established until a series of clinical observations that supported laboratory findings. In 1997, Pickup et al. [9] reported a significant association between interleukin-6 (IL-6) and type 2 diabetes. This was further supported by Kern et al. [10] who described a role of adipose-derived TNF-α and IL-6 in human obesity and insulin resistance.

At present, there is little doubt that adipose tissue is a master regulator of inflammation, and inflammation mediates insulin resistance in obesity [11]. Interestingly, this notion is not new, and a careful review of historical studies finds that Williamson [12] reported the beneficial effects of anti-inflammatory sodium salicylate on the treatment of diabetes in 1901. This review will describe recent discoveries on the underlying mechanism by which inflammation causes insulin resistance and therefore attempt to advance our understanding on a century-old notion.

JNK1 REGULATES ADIPOSE INFLAMMATION IN OBESITY

The c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) signaling pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes [13]. In obese state induced by chronic high-fat diet (HFD) or genetic manipulation, JNK1 is activated and mediates downstream signaling events that target glucose metabolism [14]. JNK1 has been shown to promote a serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), and this event inhibits insulin signaling transduction that leads to insulin resistance [15]. Consistent with this, JNK1-/- mice are protected from diet-induced insulin resistance, supporting the negative regulatory role of JNK1 on glucose metabolism [14]. However, this interpretation is not without arguments. Hirosumi et al. [14] observed that JNK1-/- mice are also resistant to diet-induced obesity. This is an important observation since the protective effects of JNK1 deficiency against diet-induced insulin resistance can be at least partially explained by the fact that JNK1-/- mice became less obese after HFD. In fact, many transgenic mouse models that are resistant to diet-induced obesity remain more insulin sensitive following HFD due to their lean phenotypes [16,17]. Therapeutic intervention that reduces obesity in HFD-fed mice also results in improved insulin sensitivity [18]. Using various genetic approaches, Roger Davis and his colleagues have extensively investigated the role of JNK1 in the context of insulin resistance in different metabolic organs. Their findings are anything but expected, and provide major advancement in our understanding of the role of JNK1 in inflammation and insulin resistance.

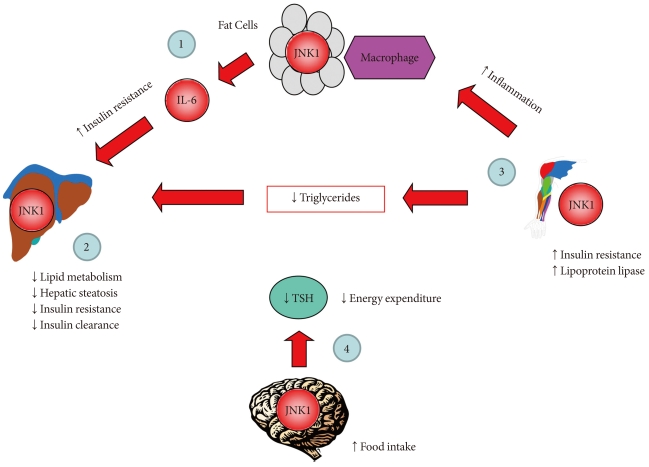

Adipose tissue is characterized by macrophage infiltration and increased cytokine secretion in obesity [19]. Adipose function of JNK1 was examined in mice with adipocyte-selective deletion of JNK1, which were generated using mice with conditional (floxed) JNK1 and adipose-specific expression of Cre recombinase (Fabp4-Cre) [20]. In these mice, JNK1 was selectively deleted in white and brown adipose tissue, while JNK1 expression was preserved in other organs [20]. Following HFD, adipose JNK1 deficient mice became obese and gained similar fat mass as compared to Cre-expressing wild-type mice. Despite becoming obese, adipose JNK1 deficient mice were more insulin sensitive, based on insulin tolerance test, after HFD [20]. Surprisingly, improved insulin sensitivity was largely due to increased insulin action in liver as shown during the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in HFD-fed JNK1 deficient mice [20]. Insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation, which is normally reduced in HFD-fed wild-type liver, was increased in JNK1 deficient mice. The mechanism by which adipose deletion of JNK1 protects liver against diet-induced insulin resistance involves adipocyte secretion of IL-6. High-fat feeding markedly elevates IL-6 mRNA and its circulating levels in obese, wild-type mice. However, JNK1 deletion in adipose tissue completely prevented diet-induced adipose secretion of IL-6, and maintained normal insulin action in liver. Thus, these findings indicate that adipose-derived IL-6 is an important mediator of diet-induced insulin resistance in liver, and that JNK1 is an important regulator of this cross-talk between adipose tissue and liver in obesity [20].

PROTECTIVE ROLE OF JNK1 IN HEPATIC STEATOSIS AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

The liver is a major organ of glucose homeostasis. In fasting state, liver produces glucose (hepatic glucose production) by breaking down stored glycogen and synthesizing new glucose from non-carbohydrate source to maintain euglycemia [21]. Following meals, hepatic glucose production is suppressed by insulin that involves insulin signaling pathway [22]. Insulin resistance and excess production of glucose by liver are the primary cause of fasting hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes [23]. Recent studies using adenoviral delivery of dominant-negative JNK or JNK-shRNA have shown that JNK1 is an important regulator of hepatic glucose metabolism [24,25]. In a recent study of Sabio et al. [26], JNK1 was selectively deleted in hepatocytes using albumin-cre as a promoter, and their findings are again remarkable. A high-fat feeding increased JNK1 activation in wild-type liver, but did not alter JNK1 activity in liver-specific JNK1 deficient mice. In contrast to previously shown negative regulatory role of JNK1 on hepatic insulin signaling using adenovirus approach, cre-lox mediated JNK1 deletion in hepatocytes failed to rescue diet-induced insulin resistance in liver [26]. Instead, JNK1 deficient mice developed insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis on chow-fed state [26]. The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp showed that this was due to reduced hepatic insulin action and blunted Akt-mediated insulin signaling in liver-specific JNK1 deficient mice. JNK1 deficiency in liver also elevated hepatic expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism (e.g., PGC-1β, PPARγ, FAS, acetyl CoA carboxylase [ACC]) that resulted in hepatic steatosis in these mice [26]. Since non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a major cause of liver dysfunction and is closely associated with metabolic syndrome [27], this newly identified role of JNK1 in regulating lipid metabolism is critical in understanding a major liver disease. Furthermore, insulin clearance by the liver is an important determinant of circulating insulin levels, and abnormal hepatic clearance of insulin has been shown to modulate peripheral glucose metabolism and obesity [28,29]. In that regard, hepatic JNK1 deficiency resulted in elevated insulin clearance that was compensated by increased insulin secretion [26]. Taken together, these findings indicate an intricate role of JNK1 in the regulation hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism.

JNK1 MEDIATES DIET-INDUCED INSULIN RESISTANCE IN SKELETAL MUSCLE

Skeletal muscle is a major organ of glucose disposal, and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle is a hallmark feature of type 2 diabetes [1]. Skeletal muscle deletion of insulin receptor or glucose transporter (GLUT4) results in insulin resistance [30,31]. In addition to adipose tissue, high-fat feeding was recently shown to increase macrophage infiltration and cause inflammation in skeletal muscle [32]. Obesity-induced macrophage infiltration in muscle was associated with increased local expression of IL-6 and TNF-α [32]. In that regard, both IL-6 and TNF-α are shown to alter insulin signaling and glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle [33,34]. IL-6 was shown to activate STAT3-SOCS3 expression and promote SOCS3-mediated downregulation of insulin signaling in isolated hepatocytes and adipocytes [35,36]. TNF-α was shown to inhibit AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and alter glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle [34]. The role of JNK1 in muscle metabolism was determined in muscle-specific JNK1 deficient mice using muscle creatine kinase (MCK-Cre) promoter [37]. A high-fat feeding caused JNK1 activation in skeletal muscle that was associated with insulin resistance in wild-type mice [37]. In contrast, diet-induced JNK1 activation was not detected in skeletal muscle of JNK1 deficient mice. Despite becoming obese, muscle-JNK1 deficient mice were protected from insulin resistance and showed increased Akt activation and glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle following HFD [37]. Interestingly, muscle JNK1 deletion resulted in increases in circulating levels of triglyceride and hepatic steatosis following HFD [37]. Muscle JNK1 deficiency also enhanced diet-induced inflammation in adipose tissue, which was responsible for blunted Akt activation in adipose tissue and liver after HFD. Therefore, these findings implicate that JNK1 mediates diet-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, and further modulates lipid metabolism that secondarily affects adipose tissue inflammation and hepatic steatosis. This unexpected combination of events in response to muscle JNK1 deficiency again reflects a complex regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism by JNK1.

NERVOUS SYSTEM JNK1 REGULATES ENERGY BALANCE VIA HYPOTHALAMIC-PITUITARY-THYROID AXIS

Of those recently identified cell-autonomous effects of JNK1, none is as intriguing and important as the role of JNK1 in the murine nervous system. Mice with whole body deletion of JNK1 are resistant to diet-induced obesity, suggesting a potential role of JNK1 in energy balance [14]. Since JNK1 deletion in adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle did not affect diet-induced weight gain, a different organ must therefore account for JNK1 regulation of diet-induced obesity. With established functions of hypothalamus and pituitary gland in regulating energy balance [38], brain is an obvious target of JNK1 effects on weight gain following HFD. This precise and logical question was addressed in mice with brain-specific deletion of JNK1 using Nestin-cre promoter [39]. Remarkably, JNK1 deficiency selectively in nervous system exactly recapitulated resistance to diet-induced obesity phenotypes observed in global JNK1-deficient mice [14]. Following HFD, mice with nervous system JNK1 deficiency remained lean as compared to wild-type littermates. Their positive energy balance was due to reduced food intake, and increased whole body energy expenditure in JNK1 deficient mice [39]. As a result of their leanness, nervous system JNK1 deficient mice were more insulin sensitive than wild-type mice after HFD [39]. Interestingly, gene expression analysis showed increased expression of mRNA derived from thyroid hormone target genes in JNK1 deficient mice. Indeed, enhanced energy expenditure in nervous system JNK1 deficient mice was due to increased thyroid hormone levels and their action [39]. Thus, these results indicate that the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is an important target of metabolic regulation by nervous system JNK1. Taken together, all of these studies clearly demonstrate that there are cell-autonomous effects of JNK1 in adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, and brain (Fig. 1). These differential and multifaceted effects of JNK1 must be carefully considered in the design of novel JNK1-related therapeutic interventions in the treatment of insulin resistance.

cJun NH2-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) regulates energy balance and glucose and lipid homeostasis via cell-autonomous manner. Based on the findings from mice with JNK1 deficiency selectively in adipose tissue, liver, skeletal muscle, or nervous system: 1) adipose tissue JNK1 promotes interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion which causes hepatic insulin resistance in obesity, 2) liver JNK1 reduces lipid metabolism and insulin clearance thereby preventing hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance, 3) skeletal muscle JNK1 mediates insulin resistance, adipose tissue inflammation, and suppresses muscle lipoprotein lipase thereby altering circulating triglyceride levels, and 4) nervous system JNK1 mediates the negative feedback regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and promotes negative energy balance by increasing food intake and reducing energy expenditure.

MOLECULAR SCAFFOLD KSR2 REGULATES ENERGY BALANCE AND GLUCOSE METABOLISM

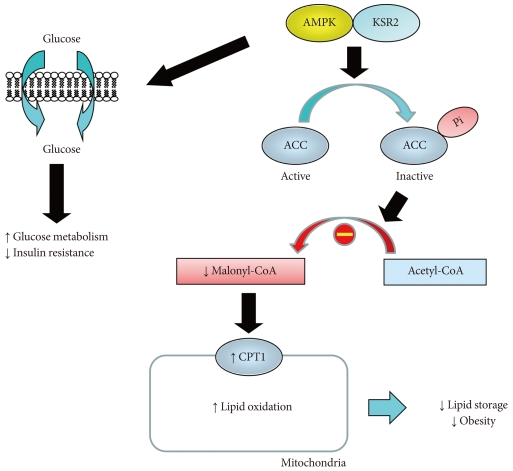

A molecular scaffold, kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (KSR2) is a critical regulator of energy balance and glucose homeostasis [40]. In both cell culture and animal models, KSR2 deficiency results in impaired energy expenditure, reduced glucose and lipid metabolism, obesity, and insulin resistance [40]. The underlying mechanism involves KSR2 regulation of AMPK, which is an important sensor of cell's nutritional status and master regulator of systemic energy balance [41]. In response to cellular stress associated with rising AMP or falling ATP, AMPK is activated and increases glucose and lipid metabolism [42]. KSR2 is shown to directly interact with AMPKα1 subunit and promotes phosphorylation of AMPK on Thr172, an essential step in AMPK signaling. The end result is inhibitory phosphorylation of ACC, a rate-limiting step in the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl CoA, and low malonyl CoA level relieves its inhibition of carnitine:palmitoyl-CoA transferase-1 (CPT1), a rate-controlling step in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation [43, 44]. AMPK also increases glucose transport and glycogen metabolism to further restore cellular energy needs [45]. Consistent with this, KSR2 deficient mice showed impaired energy expenditure and became obese. KSR2 deficient mice also developed insulin resistance in multiple organs including skeletal muscle, liver, and adipose tissue, which may be due to cell-autonomous effects of KSR2 on glucose and lipid metabolism and obesity [40].

As a master regulator of cellular metabolism, AMPK acts on multiple organs including skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, liver, heart and brain, and exerts diverse effects to maintain energy homeostasis [41]. Alterations in metabolism and energy expenditure are hallmark features of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and therapeutic activator of AMPK is actively investigated to treat metabolic disease and its complications [46,47]. Thus, the current findings on KSR2 regulation of AMPK unveil an exciting new pathway to regulate energy balance and potential drug targets (Fig. 2). More importantly, this study unveils novel insights into the role of molecular scaffold in energy homeostasis. In that regard, JNK interacting protein 1 is another scaffold protein that regulates stress kinase signaling such as JNK1 and is involved in glucose metabolism [13,48]. This is yet another evidence that other molecular scaffold proteins in the regulation of insulin resistance remain to be discovered.

Kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (KSR2) regulates obesity and insulin resistance by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). KSR2 regulates lipid metabolism by activating AMPK, which phosphorylates and inactivates acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC), and this leads to reduced malonyl CoA level that relieves its inhibition of carnitine:palmitoyl-CoA transferase-1 (CPT1), a rate-controlling step in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. As a result, KSR2 increases lipid oxidation and reduces lipid storage and obesity. KSR2-mediated AMPK activation also increases glucose metabolism and insulin action.

ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM CHAPERONE GRP78 REGULATES ENERGY BALANCE AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a specialized perinuclear organelle for the synthesis of secretory and membrane-targeted proteins. ER stress results from an imbalance between protein load and folding capacity that leads to unfolded protein response (UPR) [49]. The UPR activates 3 major ER signaling pathways: 1) PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase, 2) inositol requiring-1 (IRE-1), and 3) activating transcription factor 6 [50]. In obese state, intracellular lipid accumulation activates IRE-1 and the stress kinase signaling such as JNK1 [14]. Treatment with chemical chaperones such as 4-phenyl butyric acid or tauroursodeoxycholic acid has been shown to attenuate ER stress and improve insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice [51]. These observations implicate an important role of ER homeostasis in obesity and insulin resistance.

The 78-kDa glucose regulated protein, GRP78, also known as BiP (immunoglobulin heavy-chain binding protein) or HSPA5, is a key rheostat in regulating ER homeostasis [52]. GRP78 regulates ER function via protein folding and assembly, targeting misfolded protein for degradation, ER Ca2+ binding, and controlling the activation of transmembrane ER stress sensors [52]. To determine the role of ER stress in obesity, mice with heterozygous deletion of Grp78 were recently developed and shown to be resistant to diet-induced obesity [53]. Grp78 deficient mice showed enhanced whole body energy expenditure, and were more insulin sensitive as compared to wild-type littermates following HFD [53]. This unexpected finding in which Grp78 heterozygosity improves energy balance and insulin sensitivity is due to remarkable activation of adaptive UPR, which resulted in improved ER homeostasis in adipose tissue [53]. Thus, these findings support the important role of ER homeostasis and ER stress in energy balance and the regulation of glucose metabolism.

FUTURE QUESTIONS

If inflammation develops in white adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle, what other organs are affected by inflammation in obesity? Herrero et al. [54] recently showed that brown adipose tissue develops macrophage infiltration and inflammation in lipodystrophic mice. A recent study from our group found that diet-induced obesity causes macrophage infiltration in heart, and elevated IL-6 levels suppress AMPK activity and myocardial glucose metabolism [55]. It will be important to determine what other organs develop inflammation, and how they may contribute to insulin resistance in obesity.

If inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α mediate insulin resistance, are there cytokines that oppose the action of IL-6 and TNF-α and positively regulate insulin sensitivity? In that regard, IL-10 is a potent inhibitor of the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [56]. Plasma IL-10 levels are positively related to insulin sensitivity in healthy subjects, and IL-10 levels are reduced in obese, diabetic subjects [57,58]. A recent report from Lumeng et al. [59] demonstrated that adipose tissue macrophages from lean animals express polarization toward an alternatively activated state, and this was associated with increased expression of IL-10. This study further showed that IL-10 increases glucose uptake and protects against TNF-α mediated insulin resistance in isolated adipocytes [59]. Moreover, our recent study found that elevation of IL-10 levels by chronic IL-10 treatment or transgenic overexpression of IL-10 improves insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle following HFD [32]. It will be important to further understand the metabolic role of IL-10 and discover other cytokines that may regulate insulin resistance.

CONCLUSION

It is not presumptuous to state that diabetes is an inflammatory disease. At the cellular level, it involves a complex network of stress kinase signaling, molecular scaffolds, and ER chaperones. At the systemic level, cytokines play a major role in cross-talk between organs. Diabetes is neither an energy deficient nor energy surplus state. Instead, it is a state of energy imbalance. In the past decade, we have acquired a greater understanding of molecular events and signaling pathways to link inflammation and insulin resistance. They are new exciting ideas for an age-old question.