New Diagnostic Criteria for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Pregnancy Outcomes in Korea

Article information

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance first detected during pregnancy regardless of the degree of hyperglycemia [1] although this definition has serious limitations [2]. The age of a mother, pre-pregnancy body mass index, the amount of obesity, family history, and weight gain during pregnancy are GDM-related factors [3]. It is a common medical complication in pregnancy and is associated with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes [45] as well as lifelong risk of obesity and diabetes in both mother and child later in life [67]. Treatment of GDM has been shown to reduce adverse outcomes [8]. So, it is of great importance to diagnose this condition early and manage adequately to prevent adverse outcome.

It is estimated that GDM affects around 7% to 10% of all pregnancies worldwide [7910]. However, comparing GDM prevalence between countries has been confounded by differing sets of diagnostic criteria. The absence of universal gold standards for screening of GDM has led to heterogeneity in the identification of GDM, thereby impacting the accurate estimation of the prevalence of GDM, related health outcomes as well as their health costs.

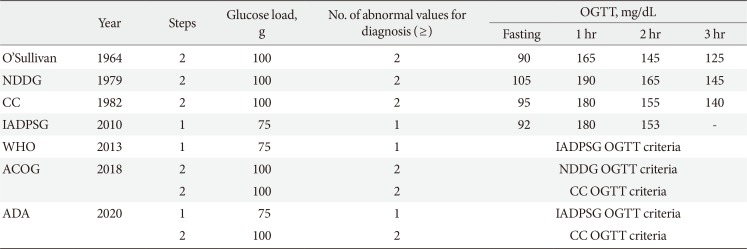

In 2010, the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) recommended universal screening of all pregnant women with the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) [11] based on the results of the international prospective Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study [12]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) in 2011 [13], the Endocrine Society [14] and the World Health Organization (WHO) [15] in 2013 accepted the IADPSG guidelines. However, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (ACOG) refuse to accept the IADPSG criteria in 2013 [1617] and has retained the two-step procedure using the thresholds of the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) [18] or Carpenter and Coustan [19] criteria. After then, the ADA in 2014 revised to agree both ACOG and IADPSG recommendations [20]; the “one-step” 75-g OGTT derived from the IADPSG [11] criteria and the older “two-step” approach with a 50-g (nonfasting) screen followed by a 100-g OGTT for those who screen positive, based on the work of Carpenter and Coustan (CC)'s interpretation [19] of the older O'Sullivan criteria [21]. Table 1 shows different diagnostic criteria of GDM. Currently, the Korean Diabetes Association indorses using both the IADPSG criteria and the CC criteria for the diagnosis of GDM.

This prospective observational cohort study done by Kim et al. [22] is the first study to investigate the number of GDM diagnoses and pregnancy outcomes in Korean women who were diagnosed with GDM by the IADPSG criteria. Between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, all women screened via the 50-g glucose challenge test regardless of fasting. Those who had glucose value above 140 mg/dL underwent diagnostic 75-g 2-hour OGTTs. GDM was diagnosed by the CC criteria. However, 3-hour glucose was not measured and was omitted form the CC criteria in this study. Women diagnosed with GDM by the CC criteria were managed according to the standard clinical practice guidelines. However, women who would be diagnosed by the IADPSG criteria but not by CC criteria were not managed as GDM patients and only had routine prenatal obstetric care. They stratified participants into three groups of (1) women with no GDM by either the IADPSG criteria or the CC criteria (no GDM group); (2) women exclusively diagnosed with GDM by the IADPSG criteria and not by the CC criteria (IADPSG GDM group); and (3) women diagnosed with GDM by the CC criteria (CC GDM group). The IADPSG criteria increased the incidence of GDM by nearly three-fold (the incidence of GDM was 2.1% according to CC criteria, and additionally 6.2% by the IADPSG criteria). Compared to the no GDM group, women in the IADPSG GDM group had an increased risk of preeclampsia, and neonates had an increased risk of large for gestational age, macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia. This study had several limitations; the IADPSG criteria were not applied as a one-step approach and a 75-g OGTT was used instead of a 100-g OGTT in CC criteria.

In summary, IADPSG universally increased the prevalence of GDM. When applying the IADPSG criteria in Korea, the prevalence of GDM must be increased and it will be necessary to evaluate the cost effectiveness of treating GDM diagnosed by IADPSG criteria. Women with a past history of GDM had a 50% increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes within 7 to 10 years of pregnancy [23] and a seven-fold increased risk of developing it compared to normal glucose tolerance of pregnancy [24]. Further, it will also be necessary to investigate postpartum risk of diabetes or prediabetes according to IADPSG diagnostic criteria in Korea.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.