Subjective Assessment of Diabetes Self-Care Correlates with Perceived Glycemic Control but not with Actual Glycemic Control

Article information

Abstract

Background

We investigated whether patients' perceived glycemic control and self-reported diabetes self-care correlated with their actual glycemic control.

Methods

A survey was administered among patients with diabetes mellitus at an outpatient clinic with structured self-report questionnaires regarding perceived glycemic control and diabetes self-management. Actual glycemic control was defined as a change in glycated hemoglobin (A1C) or fasting plasma glucose (FPG) since the last clinic visit.

Results

Patients who perceived their glycemic control as "improved" actually showed a mild but significant decrease in the mean A1C (-0.1%, P=0.02), and those who perceived glycemic control as "aggravated" had a significant increase in the mean FPG (10.5 mg/dL or 0.59 mmol/L, P=0.04) compared to the "stationary" group. However, one-half of patients falsely predicted their actual glycemic control status. Subjective assessment of diabetes self-care efforts, such as adherence to a diet regimen or physical activity, correlated positively with perceived glycemic control but showed no association with actual glycemic control.

Conclusion

Patients should be encouraged to assess and monitor diabetes self-care more objectively to motivate behavioral modifications and improve their actual glycemic control.

INTRODUCTION

The way diabetes patients assess glycemic control in their ordinary lives, as well as whether their perceived glycemic control predicts actual glycemic control, has been debated extensively. The accuracy of patients' subjective glycemic control is critical because if, for example, a patient has a falsely favorable assessment of his or her glycemic control, then he or she will not be motivated to improve their glycemic control through behavioral changes, leading to poorer actual glycemic control.

In previous studies, patients' evaluations of diabetes self-management were significantly associated with actual glycemic control, and the usefulness of patients' evaluations of diabetes self-care for improving glycemic control was emphasized [1,2]. On the other hand, in a recent study of minority patients with diabetes, patients' perceptions of diabetes control were determined by subjective cues, such as the perceived impact of diabetes or adherence to a diabetes diet, which are not related to actual glycemic control, and actual glycemic control was directed by objective cues, such as age or insulin use [3].

Diabetes self-management includes monitoring blood glucose levels, engaging in regular exercise, following a regular and healthful dietary regimen, taking medications, and caring for the feet. Diabetes self-management training has been shown to be effective in improving glycemic control, especially in the short term [4,5,6,7].

The aim of this study was to investigate the associations among recent actual glycemic control (a change in glycated hemoglobin [A1C] level from the last clinic visit) and perceived glycemic control and diabetes self-care. Patients' perceptions of glycemic control and diabetes self-care were evaluated with a structured questionnaire, and their A1C levels were retrieved from medical records.

METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional study and a self-report survey was administered among patients with type 2 diabetes at the outpatient clinic of Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine from June to September 2011. Patients with the following characteristics were included in the study: diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at least 1 year ago; no change in medication during the previous 6 months; no change in insulin regimen or a dosage change of no more than two units if on insulin therapy; access to both current and previous (2 to 4 months ago) A1C levels; and no cognitive impairment. Patients who had been on medication affecting glucose metabolism (e.g., glucocorticoids) or had events such as surgery or infection that could also affect glycemic control were excluded from the study.

Approval for the study was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, study participants signed the informed consent and all patient data remained anonymous.

The survey questionnaire was composed primarily of two parts: a self-report questionnaire about the subjective glycemic control status and 9-item questions about diabetes self-management adapted from the Korean-translated version of the revised Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure (SDSCA), which is well validated [8,9]. Perceived glycemic control was assessed with the question, "How do you think your glycemic control has been since your last visit?" and patients were asked to respond with one of three answers: improved, no change, or aggravated. Diabetes self-management was evaluated based on the following aspects: the general diet (one item), specific diet (vegetable, low-fat diet; one item for each diet), physical activity (two items), blood-glucose check (one item), foot care (two items), and adherence to medication (one item). Participants were asked about the number of days per week they had performed self-care activities; "0" indicated no performance, while "7" indicated daily performance. Objective glycemic control was assessed by any recent change in A1C or fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels since the patients' last clinic visit 2 to 4 months ago.

The mean values of continuous variables among groups were compared with an independent sample t-test or one-way analysis of variance, and the associations between categorical variables were analyzed with the chi-square test. Correlations between continuous variables were tested by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients and their P values with correlation analysis. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the study subjects

A total of 272 patients completed the survey. The mean age of the study participants was 64 years, and on average, they had had diabetes for 11 years and the average body mass index (BMI) was 24 kg/m2. Males comprised 46.3% of the respondents. The proportion of participants taking only oral antidiabetic medications was 71.2%, and 22.3% were using insulin, while others (6.6%) were not taking any antidiabetic medications. The mean±standard deviation of A1C at the time of the survey was 7.2%±0.9%, while on the previous clinic visit it was 7.2%±0.9%.

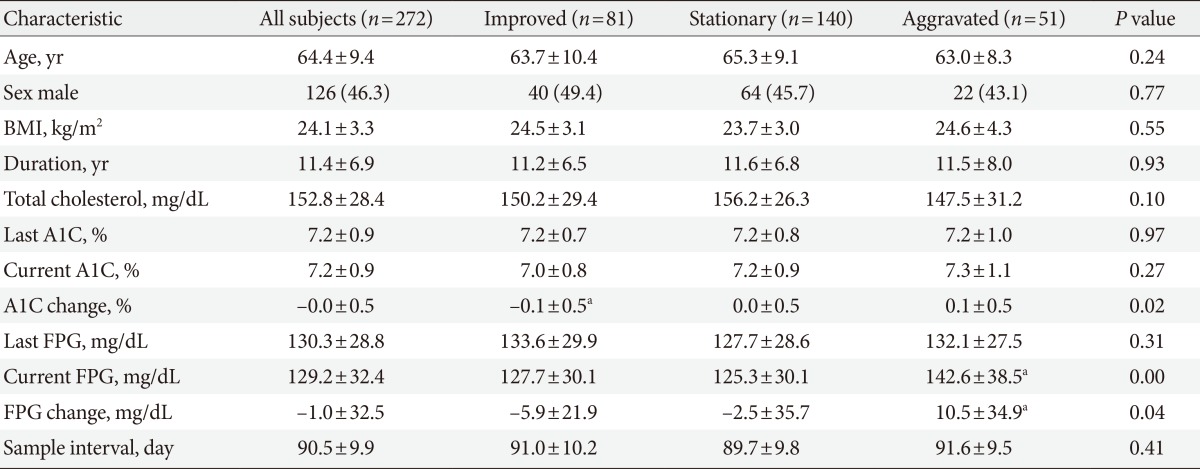

Eighty-one patients perceived better glycemic control since their last clinic visit, and 140 patients replied that their glycemic control would not reflect any change, while 51 patients guessed their glycemic control was worse. Table 1 summarizes the participants' demographic data according to subjective glycemic control. Age, sex, BMI, years with diabetes, and serum cholesterol did not differ significantly among the three groups.

Relationship between actual and perceived glycemic control

Actual glycemic control is defined as a change in A1C and FPG since the patient's last clinic visit. The mean A1C and FPG at previous clinic visits 2 to 4 months ago did not vary much across the three groups (Table 1). Patients with better perceived glycemic control showed a mean decrease of -0.1% in A1C (P<0.05) and 5.88 mg/dL (0.33 mmol/L) in FPG, while patients who perceived their glycemic control to be worse exhibited a mean increase of 0.1% in A1C and 10.55 mg/dL (0.59 mmol/L) in FPG (P<0.05). Overall, although absolute changes were moderate, the change in A1C and FPG was significantly different among the three groups, with actual and perceived glycemic control showing a positive correlation.

The misperception rate of glycemic control

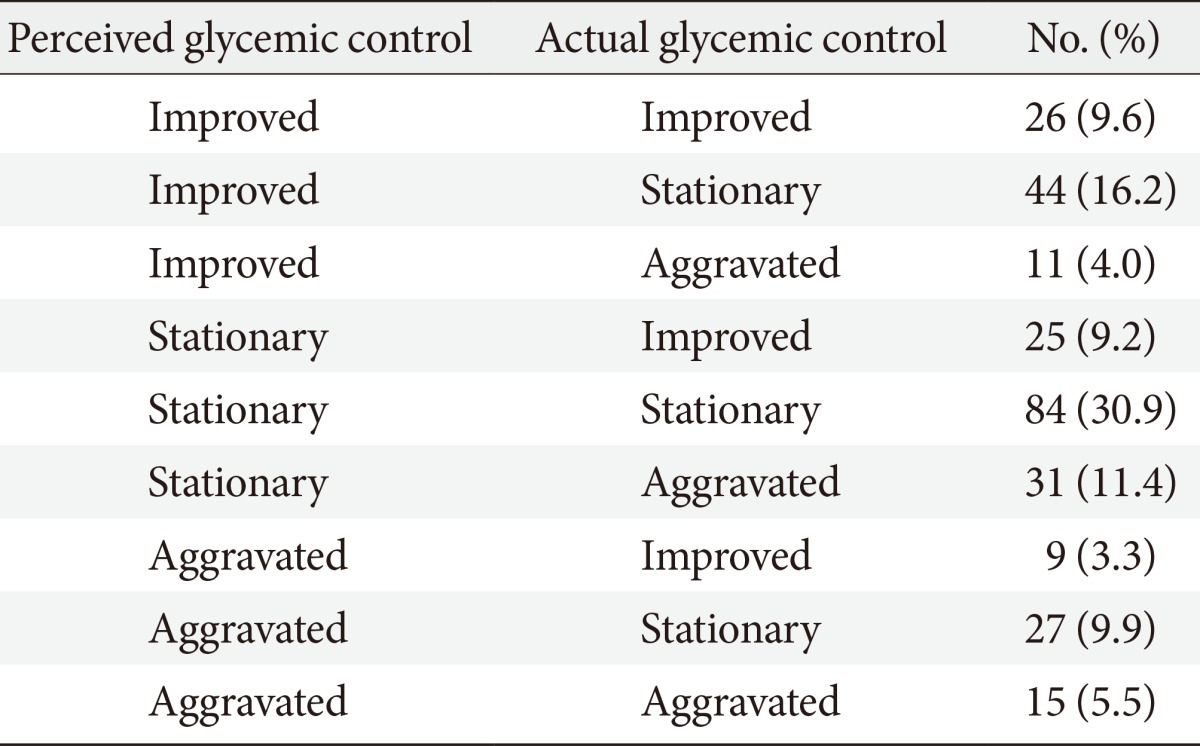

As the differences in A1C and FPG changes were only moderate among groups with different perceived glycemic control, we investigated the misperception rate of glycemic control in study participants. Patients are classified as the "correct perception group" if their perceived glycemic control was equal to their actual glycemic control and were otherwise classified as the "misperception group." Actual glycemic control was categorized into three groups, "improved," "no change," or "aggravated," similar to the perceived glycemic control categories. We defined a significant change in actual glycemic control as one wherein the glycated hemoglobin changed by the cutoff of 0.4%. Table 2 summarizes the number of participants according to their classification in the perceived or actual glycemic control groups. We arbitrarily chose 0.4% as a cutoff of A1C change for the assessment of a significant change in actual glycemic control as a misperception rate, and the clinical characteristics were similar in the two groups at other cutoffs of 0.3% and 0.5%. The misperception rate at the A1C cutoff of 0.4% was 54.0% and the misperception rates were 57.7% and 51.8% at respective A1C cutoffs of 0.3% and 0.5%.

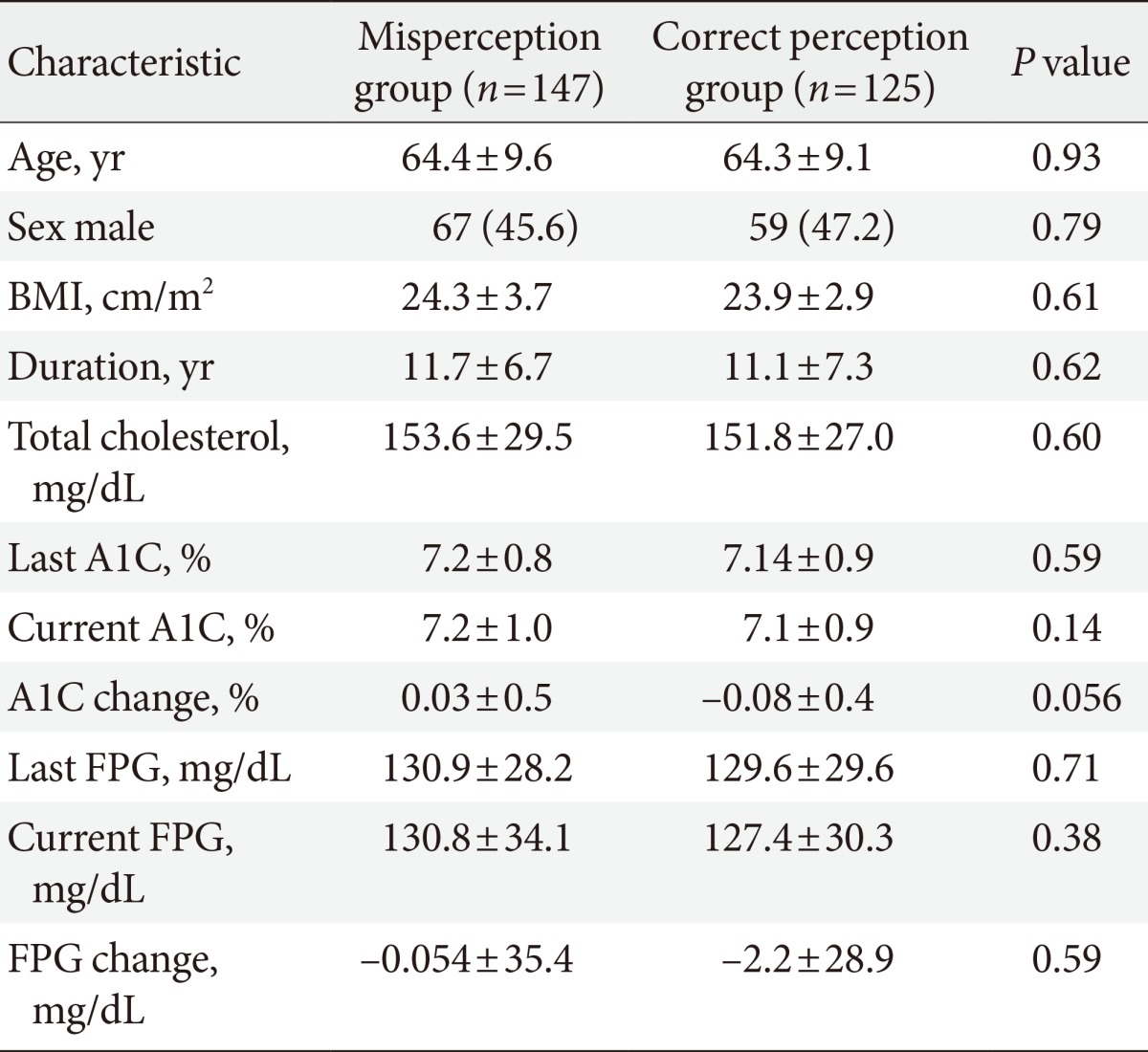

Such high misperception rates of glycemic control are worrisome, as misperceptions will affect the self-care behavior of diabetes patients, especially if a patient falsely assesses his or her glycemic control as better than it is and does not attempt to modify their current life style [10]. Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics in the misperception or correct perception groups at the A1C cutoff of 0.4%, and the clinical traits did not differ between the two groups.

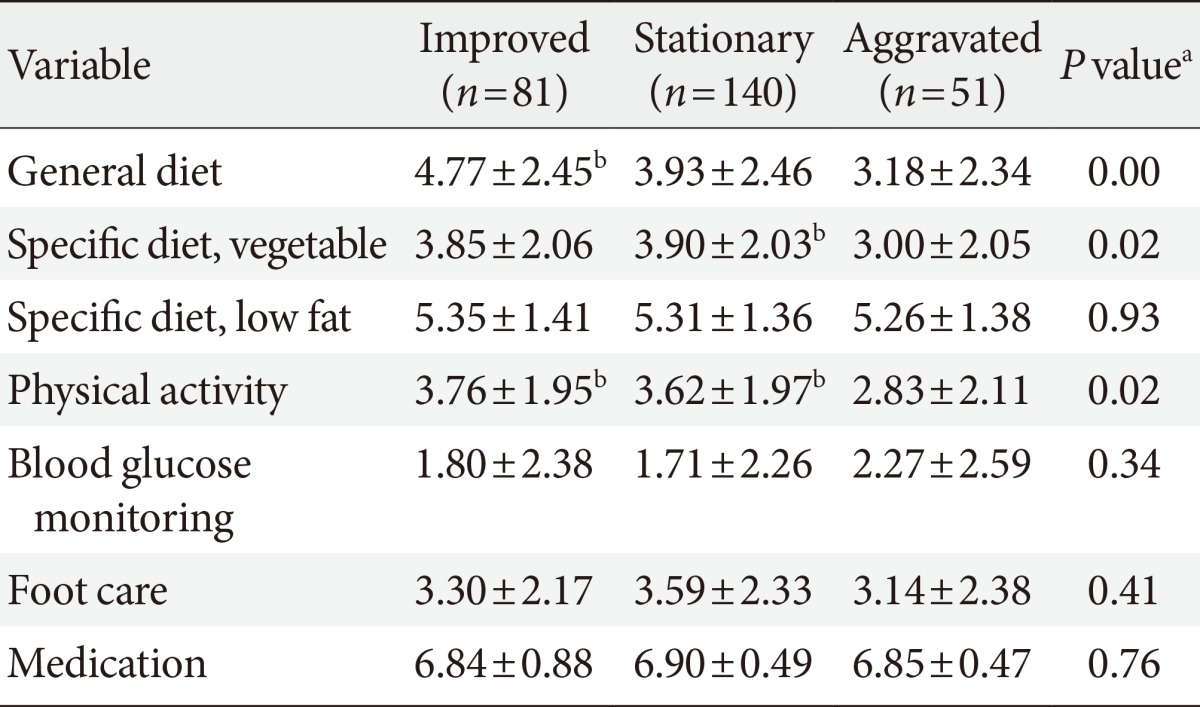

The association between perceived glycemic control and the subjective assessment of diabetes self-care

The subjective assessment of diabetes self-care was evaluated by the Korean version of the revised SDSCA questionnaire [8,9]. The mean±standard deviation for each category of diabetes self-care was as follows: 4.04±2.39 in general diet, 3.51±2.01 in physical activity, 1.84±2.36 in blood glucose check, 3.42±2.29 in foot care, and 6.87±0.63 in medication adherence. Table 4 summarizes the patients' assessment scores of diabetes self-care by the three groups of perceived glycemic control. Patients who perceived better or worse glycemic control reported significantly higher or lower scores of diabetes self-care assessments in their general diet, specific diet (vegetable), and physical activity, respectively. However, the subjective assessments of foot care, blood glucose self-monitoring, and medication compliance were not significantly different among the three groups of perceived glycemic control. This suggests that patients assess their glycemic control by their adherence to a diabetes diet regimen or physical activity.

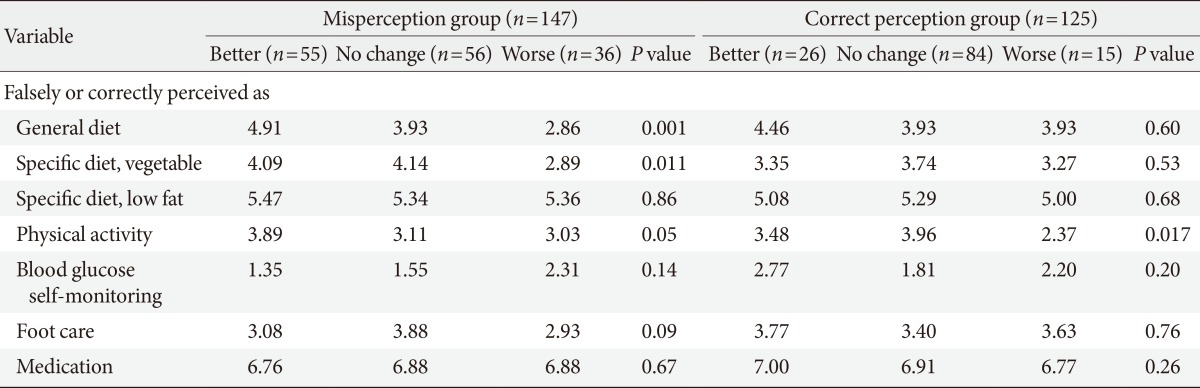

The subjective assessment of diabetes self-care was investigated in patients who correctly or falsely perceived glycemic control. Table 5 shows the SDSCA scores in each category of correct or false perceived glycemic control patients. Patients with the false perception that their glycemic control was better than was actually the case had even more favorable assessments of their self-care regarding general and specific diets and exercise than those who correctly perceived their glycemic control as better (for example, general diet, 4.91 vs. 4.46; physical activity, 3.89 vs. 3.48) This result highlights the necessity of finding a way to encourage the group of patients with false perceptions of glycemic control to evaluate their diabetes self-management in a more objective and realistic manner, such as keeping a food or physical activity diary.

The subjective assessment of diabetes self-care is not correlated with actual glycemic control

The next research question was whether patients' assessments of diabetes self-care are associated with actual glycemic control. The correlations between actual glycemic control, defined as a change in A1C or FPG, and assessment scores of diabetes self-care were not significant at a P value cutoff of 0.05, and only the self-assessment score for foot care was marginally correlated with a change in FPG (Pearson correlation coefficient= -0.125, P=0.039). This suggests that actual glycemic control is determined by different cues than perceived glycemic control.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to explore whether type 2 diabetes patients' perceptions of glycemic control predicts actual glycemic control through the administration of a self-reported questionnaire. Patients who perceived glycemic control as "improved" showed a mild but significant decrease in A1C, and those who predicted their glycemic control as "aggravated" had a significant increase in FPG compared to the group who thought their glycemic control did not change significantly. Of particular interest from our study is the fact that about half the diabetes patients misperceived their actual glycemic control. Patients' perceptions of glycemic control were associated with their subjective assessment of diabetes self-care behavior, especially diet and exercise. However, the subjective assessment of diet and exercise did not correlate with actual glycemic control, and patients who misperceived glycemic control under- or over-estimated diabetes self-care.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that improvements in diabetes self-care practices such as diet, exercise, self-monitoring of blood glucose, foot care, and medication compliance, enhance glycemic control [4,5,6,7]. However, the finding that the subjective assessment of diabetes self-care, which is associated with subjective glycemic control, does not correlate with actual glycemic control, as well as the findings that half of patients misperceive their glycemic control and patients who falsely predict glycemic control as better have more favorable assessments of self-care than those with worse perceived glycemic control, suggest that it is necessary to encourage patients to monitor their self-care behavior in an objective, realistic, and quantitative manner.

To enhance the objective assessment of self-care behavior, especially diet and exercise, diabetic patients should be encouraged to keep a food and physical activity diary [5,11]. Reflection of diabetes self-care based on objectively collected data will motivate patients' behavioral changes, leading to an improvement in glycemic control. These days, mobile devices for real-time collection and the storage of life-log data on physical activity, blood glucose, and diet are rapidly being developed. Favorable outcomes of studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of ubiquitous health services in improving glycemic control suggest that the incorporation of mobile devices into diabetes care to help patients collect life-log data on physical activity, diet, and blood glucose will enable patients to monitor their self-care more objectively, leading to better glycemic control [12,13].

A strength of our study is that we evaluated patients' diabetes self-care assessments with well-validated self-report questionnaires (SDSCA). Additionally, actual glycemic control is defined as the change in A1C from the previous A1C to reflect the most recent glycemic control, unlike other studies that defined actual glycemic control based on a recent A1C value which may not reflect current glycemic control. A limitation of the study is the lack of information on each patient's level of education, as that might affect his or her perception of glycemic control and self-care activity. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we could not observe whether a more realistic and objective analysis of self-care assessment would enhance the accuracy of patients' perceived glycemic control. Further, the absolute change in A1C from the previous clinic visit was approximately 0.1%, which was relatively small, and it may be partly explained by the good glycemic control of study participants at baseline. We did not intend to enroll subjects with good glycemic control; however, the baseline A1C was 7.2% on average, which may have been affected by the inclusion criteria of no change in medication since last the clinic visit to exclude the effect of medication adjustment on glycemic control.

In conclusion, we found a weak but significant correlation between perceived glycemic control and actual glycemic control. However, half of the diabetes patients in the study misperceived their glycemic control and falsely predicted their actual glycemic control, with subjective assessments of diabetes self-care practices, such as diet and exercise, being exaggerated in the group demonstrating misperceptions.

Based on the present survey, we underscore the importance of adopting ways to objectively and quantitatively monitor patients' diabetes self-care behaviors and to help patients assess their glycemic control on the grounds of such objective data. Future study is warranted to test whether improvements in the objective assessment of self-care behavior will enhance the accuracy of perceived glycemic control and, eventually, actual glycemic control.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.