Various Oscillation Patterns of Serum Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Concentrations in Healthy Volunteers

Article information

Abstract

Background

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) was originally identified as a paroxysm proliferator activated receptor-α target gene product and is a hormone involved in metabolic regulation. The purpose of this study was to investigate the diurnal variation of serum FGF21 concentration in obese and non-obese healthy volunteers.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from five non-obese (body mass index [BMI] ≤23 kg/m2) and five obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) healthy young men every 30 to 60 minutes over 24 hours. Serum FGF21 concentrations were determined by radioimmunoassay. Anthropometric parameters, glucose, free fatty acid, insulin, leptin, and cortisol concentrations were also measured.

Results

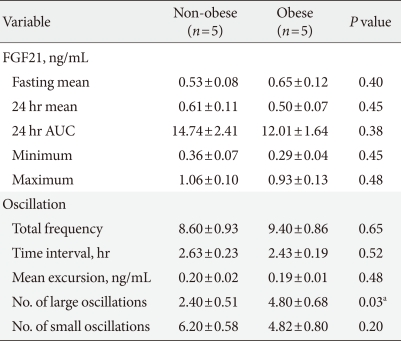

The serum FGF21 concentrations displayed various individual oscillation patterns. The oscillation frequency ranged between 6 and 12 times per day. The average duration of oscillation was 2.52 hours (range, 1.9 to 3.0 hours). The peaks and troughs of FGF21 oscillation showed no circadian rhythm. However, the oscillation frequency had a diurnal variation and was lower during the light-off period than during the light-on period (2.4 vs. 7.3 times, P<0.001). There was no difference in the total frequency or duration of oscillations between non-obese and obese subjects, but obese individuals had increased numbers of larger oscillations (amplitude ≥0.19 ng/mL).

Conclusion

Various oscillation patterns in serum FGF21 concentration were observed, and reduced oscillation frequencies were seen during sleep. The oscillation patterns of serum FGF21 concentration suggest that FGF21 may be secreted into systemic circulation in a pulsatile manner. Obesity appeared to affect the amplitude of oscillations of serum FGF21.

INTRODUCTION

Fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) is a 210-amino acid peptide belonging to the FGF19 family [1]. In rodents, FGF21 mRNA is widely expressed in peripheral metabolic tissues, such as the liver, pancreas, skeletal muscle, and white adipose tissue [1-3]. FGF21 protein also has been detected in plasma [4], which suggests that it is secreted into systemic circulation and may act like a hormone. Indeed, FGF21 binds to FGF receptors and its coreceptor β-klotho on plasma membranes [5,6], activating Akt signaling pathways [7].

Prolonged fasting was found to increase hepatic FGF21 transcription in rodents, and this increased transcription was mediated by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α (PPARα) [8]. Elevated FGF21 levels during fasting appear to be important for metabolic adaptation to a low energy state by inducing increased ketogenesis, lipolysis, and torpor-like behavior [9,10]. On the other hand, accumulated data demonstrate the beneficial effects of FGF21 on glucose and lipid metabolism [11,12]. FGF21-overexpressing mice were resistant to the development of diet-induced obesity [13]. Treatment of adipocytes with FGF21 stimulated glucose uptake in an insulin-independent manner. Moreover, FGF21 treatment in a mouse model of diabetes mellitus improved insulin resistance and lowered plasma glucose and triglyceride concentrations [13]. Similarly, the treatment of diabetic monkeys with FGF21 corrected insulin resistance and improved β-cell function. These results indicate that FGF21 may be a promising target in the treatment of diabetes mellitus [12].

In humans, morning fasting serum FGF21 concentrations were not significantly altered by short-term fasting but were increased by treatment with the PPARα ligand fenofibrate [14]. Circulating FGF21 concentrations also were elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes compared to non-diabetic individuals and were negatively correlated with fasting blood glucose concentration [15]. Moreover, fasting serum FGF21 levels were positively associated with parameters of obesity, such as body mass index (BMI) and waist to hip ratio (WHR) [16,17], although another study reported no such correlation [14]. However, the physiological roles of FGF21 in human metabolism remain obscure.

Serum concentrations of hormones engaged in metabolic regulation often display unique diurnal patterns, from which we can infer their physiological roles. For example, serum insulin concentrations are elevated after meal intake but suppressed during fasting [18]. This diurnal pattern of insulin is indicative of its critical role in postprandial glucose disposal. In contrast, elevated plasma glucagon and cortisol concentrations during fasting suggest that these hormones are important formetabolic adaptation to fasting [19]. Circulating concentrations of the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin also are increased just before food ingestion [20], a finding that is compatible with its role as a meal initiator.

Aberrant circadian rhythms are closely associated with metabolic abnormalities and obesity [21,22]. Hepatic FGF21 expression was recently shown to be regulated by clock transcriptional factors, such as retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-α (RORα) and Rev-Erbα [23,24]. A previous study investigated serum FGF21 concentrations over 24 hours in five non-obese subjects and found that serum FGF21 levels oscillated but were stable throughout the day, without definite diurnal variations or meal-related changes [14]. That study, however, did not investigate the 24 hour profile of serum FGF21 concentrations in obese subjects. Therefore, in the present study, we compared serum FGF21 concentrations over 24 hours between obese and non-obese healthy volunteers.

METHODS

Study subjects

Five non-obese and five obese healthy male volunteers were recruited through website advertisements, as described previously [25]. At the first visit, anthropometric parameters were measured before breakfast, with the subjects wearing light clothing and no shoes. The BMI of each subject was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Non-obese individuals were defined as having a BMI of 18.5 to 22.9 kg/m2, and obese individuals were defined as having a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2, in accordance with the definition for Asian adults proposed by the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization (WPRO) [26]. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at the level of the greatest frontal extension of the abdomen between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest; hip circumference was measured at the level of the widest part of the hips. Blood pressure was measured from the right arm after a 20 minute rest. Metabolic disorders were screened by collecting blood samples from all subjects after an overnight (10 hours) fast. Plasma and serum were immediately separated and stored at -70℃ until measurement.

Inclusion criteria were: 1) age of 18 to 60 years; 2) BMI of 17 to 23 kg/m2 for the non-obese group and 25 to 40 kg/m2 for the obese group; and 3) no clinical evidence of other medical conditions, such as hypertension; diabetes mellitus; pulmonary, cardiovascular, liver and renal diseases; or alcohol or drug abuse. Exclusion criteria included: 1) a ≥5% weight loss over at previous 3 months; 2) current medication, including herbal, nutritional, or vitamin supplements; 3) psychiatric illness; 4) gastrointestinal surgery; 5) smoking; 6) heavy alcohol consumption (>2 drinks per day); and 7) intensive exercise (≥30 minutes, ≥3 times per week).

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Study design and blood sampling

Before admission, eating behaviors and diet patterns were evaluated by a dietician by recording the diet for 3 days. The dietician instructed the subjects to consume a diet composed of 60% carbohydrate, 25% fat, and 15% protein to maintain current body weight for 1 week before participation in the study. At the end of the one-week diet control period, all subjects were admitted to the Asan Clinical Research Center at 17:00 hour 1 day before study initiation and were provided with dinner. After an overnight fast, blood sampling began at 07:00 hour the next morning. Blood samples were obtained every 30 minute from 07:00 to 21:00 hour and then every hour until 07:00 hour the next morning. During a study day, a meal was provided at 08:00, 12:30, and 18:00 hour, without snacks. The subjects spent their time in bed, except during waste elimination. Lights were off from 22:00 to 06:00 hour.

Assays

Blood samples were collected in serum-separating tubes containing aprotinin (250 kallikrein inhibitor units; Sigma-Aldrich, Seoul, Korea). Serum FGF21 concentrations were assayed with a radioimmunoassay kit (Phoenix Europe, Karlsruhe, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The lower and upper detection limits of FGF21 were 0.23 and 30 ng/mL, respectively. Fasting glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol were measured enzymatically with an auto-analyzer (Hitachi E170; Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Serum-free fatty acid (FFA) was measured by enzyme immunoassay with Viva-E (Dade Behring Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA). Commercial radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits were used to measure levels of insulin, leptin (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO, USA) and cortisol (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). The 24 hour integrated area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by the trapezoid method. The oscillatory patterns of serum FGF21 in the non-obese and obese groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Spearman's correlation coefficient analysis was performed to determine the factors associated with serum FGF21 levels. SPSS version 14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

The average age (mean±SEM) of the subjects was 23±1 years; their baseline anthropometric and biochemical findings were presented in our previous paper [25]. The average BMIs of the non-obese and obese groups were 21.9±0.6 and 29.8±1.4 kg/m2, respectively, and the average waist circumferences were 80.4±2.1 cm and 98.4±2.8 cm, respectively. Compared to the non-obese group, the fasting plasma leptin concentrations were significantly higher in the obese group; the fasting insulin, glucose, FFA, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations tended to be higher in the obese group (data not shown).

24 hour profiles of serum FGF21 concentration

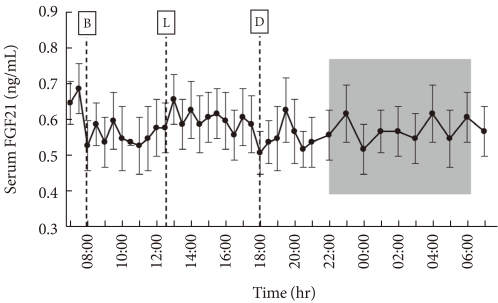

Among all subjects, the average fasting morning serum FGF21 concentration was 0.58±0.01 ng/mL (range, 0.44 to 0.94 ng/mL). The serum FGF21 concentrations showed oscillating patterns over 24 hours, with a frequency of oscillation of 6 to 12 times per day (Fig. 1). The average FGF21 excursion value between peak and trough was 0.19±0.01 ng/mL (range, 0.13 to 0.27 ng/mL). The average time interval between peaks was 2.4 hours, with large inter- and intra-individual variations. Although the peaks and troughs of serum FGF21 oscillations did not show a definite circadian rhythm (Fig. 1), the oscillation frequencies were significantly reduced (2.4 vs. 7.3 times, P<0.001) and the average duration of oscillations was increased (3.5 vs. 1.8 hours, P<0.001) in the light-off period compared to the light-on period.

The 24 hour profiles of serum fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and other metabolite concentrations in 10 healthy male volunteers. The subjects consumed breakfast (B), lunch (L), and dinner (D) at the times indicated. The shaded area represents the lights-off period.

The individual profiles of serum FGF21 levels are presented in Fig. 2. There were larger inter-individual variations in diurnal rhythms and oscillation patterns of circulating FGF21. The peak serum FGF21 concentrations declined with daily progression in non-obese subject #2 (L2) and obese subject #1 (O1), but none of the other subjects showed a definite diurnal pattern. L1, L5, O2, and O5 showed smaller and more frequent oscillations, whereas L3, L4, O1, O3, and O4 had larger and less frequent oscillations (Fig. 2).

Individual diurnal pattern of serum fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). Note the inter-individual variation and the heterogeneity of the oscillation patterns. Serum FGF21 profiles of non-obese (L) subjects are shown in the left panels, whereas those of obese (O) subjects are shown in the right panels. B, breakfast; L, lunch; D, dinner.

When we compared serum FGF21 concentrations in the obese and non-obese groups, we found no significant difference in the mean, maximum, minimum, or AUC values between the two groups (Table 1). In addition, the oscillation parameters, including the total oscillation frequency, duration, and excursion values, did not differ between the obese and non-obese groups (Table 1).

Because the mean excursion value of serum FGF21 was 0.19 ng/mL, we defined a large oscillation as an excursion value ≥0.19 ng/mL and a small oscillation as an excursion value <0.19 ng/mL. As shown in Table 1, the frequency of large oscillations was greater in the obese than in the non-obese group (4.8±0.7 vs. 2.4±0.5 times, P<0.05).

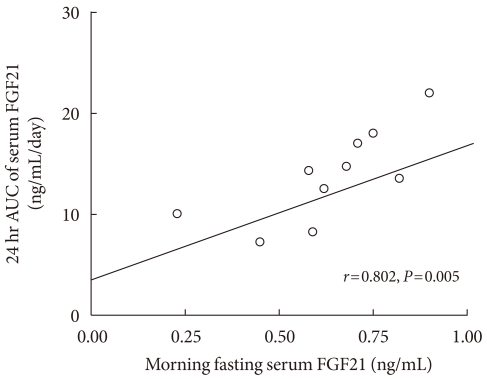

Correlation of serum FGF21 levels and metabolic parameters

We observed a significant correlation between the morning fasting levels (average values at 07:00, 07:30, and 08:00 hour) and the 24 hour integrated AUC values of serum FGF21 (Fig. 3). Fig. 4 shows the 24 hour profiles of FFA, glucose, insulin, leptin, and cortisol, together with those of FGF21. The correlation coefficient analyses showed that the fasting and 24 hour integrated AUC levels of serum FGF21 were not significantly associated with other factors, such as fasting blood lipid profiles, insulin, leptin, cortisol, glucose, BMI, or WHR (data not shown). Notably, the fasting FFA level was significantly correlated with 24 hour AUC values of serum FGF21 (r=0.673, P<0.05).

Correlation of average morning fasting concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) with 24 hour area under the curve (AUC) values.

DISCUSSION

The present study reports the 24 hour profiles of circulating FGF21 in 10 healthy subjects. Inconsistent with previous report [14], we found oscillating patterns in the serum FGF21 concentrations. The frequency of oscillation ranged from 6 to 12 times per day, with an average oscillation duration of about 2.5 hours. An earlier study [14] missed many oscillations perhaps because they collected blood samples every 90 minute. Although some individuals showed diurnal variations in the peak and trough levels of oscillation of serum FGF21, there was no consistent circadian pattern. Notably, the oscillation frequency was significantly diminished and the oscillation duration was prolonged during sleep; these findings suggest that the changes in oscillation frequency may represent diurnal variations.

In contrast to our findings, two recent papers have demonstrated a circadian rhythm in serum FGF21 levels. The levels reached a nadir in late afternoon and a peak in early morning [27,28]. In those studies, the oscillatory patterns of serum FGF21 were not clearly analyzed. The reason for the discrepancy in the circadian variations of FGF21 is unclear at present but may be due to the differences in the FGF21 assay and study subjects used.

Several papers have investigated the mechanisms regulating hepatic FGF21 mRNA expression. Fasting was shown to increase serum FGF21 levels in rodents, which may be mediated via PPARα activation [9]. Similarly, the administration of the PPARα ligand bezafibrate was found to increase hepatic FGF21 mRNA [8]. This effect was only significant when bezafibrate was administered at the onset of night. As an endogenous ligand of PPARα, FFA may also affect FGF21 production or secretion. Yu and colleagues [27] have shown that serum FGF21 levels are temporally correlated with serum FFA. They also demonstrated that treatment with the linoleate increased FGF21 mRNA and protein levels in HepG2 hepatocytes and stimulated FGF21 secretion from the cells [29]. Similarly, we found that 24 hour AUC values of FGF21 were significantly correlated with the fasting FFA levels.

FGF21 production is known to be under circadian regulation. Rev-Erbα, an important regulator of circadian rhythm, suppresses FGF21 expression by directly binding to the promoter region of the FGF21 gene promoter region [23]. Another clock transcriptional factor, RORα, stimulates FGF21 mRNA and secretion [24]. These findings suggest that FGF21 production may be controlled in a circadian manner. However, the physiological mechanisms responsible for FGF21 secretion from the cells and the oscillatory pattern in serum FGF21 concentration remain unknown.

When we compared the circulating FGF21 concentrations and oscillation patterns between obese and non-obese subjects, we found no difference between groups in the mean, maximum, minimum, or 24 hour integrated AUC values of serum FGF21. Interestingly, the number of larger oscillations was significantly greater in obese subjects, suggesting that obesity may influence the magnitude rather than the frequency or duration of oscillations. In contrast, Yu et al. [27] found that daytime serum FGF21 levels were elevated and a nocturnal rise was blunted in obese subjects.

Obesity is associated significantly with increased circulating FGF21 concentrations in rodents. However, in humans, the relationship between circulating FGF21 and BMI (a marker of adiposity) remains unclear. For example, one study in 76 healthy non-obese subjects found that the serum FGF21 levels did not correlate with BMI [14], whereas other studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between these values [15-17,30]. Such discrepancies may be due to differences in the sample sizes or subject characteristics or to the relatively large interindividual variations of serum FGF21 concentrations. In our study, the obese subjects were not severely obese (average BMI~30 kg/m2) and were relatively metabolically healthy and young. Because there are certain obese individuals with normal metabolic profiles and vice versa [14,16], it may be worthwhile to stratify FGF21 concentration not just by BMI but also by metabolic profile. Indeed, we found that the subjects with higher serum FFA levels had higher FGF21 levels, independent of BMI.

Our study may be limited by the small number of subjects and the short observation period. However, our findings are valuable in that they represent the first analysis of the oscillation patterns of serum FGF21 in non-obese versus obese subjects.

In summary, the oscillation frequency of serum FGF21 concentration had diurnal rhythm, and the magnitude of the oscillation was affected by adiposity. These findings suggest that the oscillation patterns of serum FGF21 in humans may be affected by metabolic conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Bok Soon Son and Jin A Kong for their helpful assistance. This study was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean government (2009-0079566, 2007-0056866).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.